Reposted from U of U Health.

A few months after the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the United States in early 2020, some people who appeared to have recovered from the SARS-CoV-2 viral infection began reporting that they had a constellation of persistent symptoms.

Soon after, these tenacious health problems, which included fatigue, memory loss, shortness of breath, and loss of the sense of smell and taste, were referred to as long COVID.

Since then, an estimated 14 million Americans who survived the virus have developed long COVID, according to an analysis conducted by The Washington Post in conjunction with Epic Systems, an electronic health records company, and the Kaiser Family Health Foundation. Of those, at least 3,500 people have died from long COVID complications, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

While treatment at clinics that specialize in long COVID is available in most states, including at University of Utah Health, the underlying cause of the malady remains a mystery.

However, in a small study, U of U Health scientists recently detected a potentially important clue.

The scientists found that levels of a particular set of proteins that are crucial in controlling the growth and activity of immune system cells were almost undetectable among individuals who had long COVID. As a result, the researchers suspect that lungs and other organs are unable to fully heal and fend off other illnesses after being infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

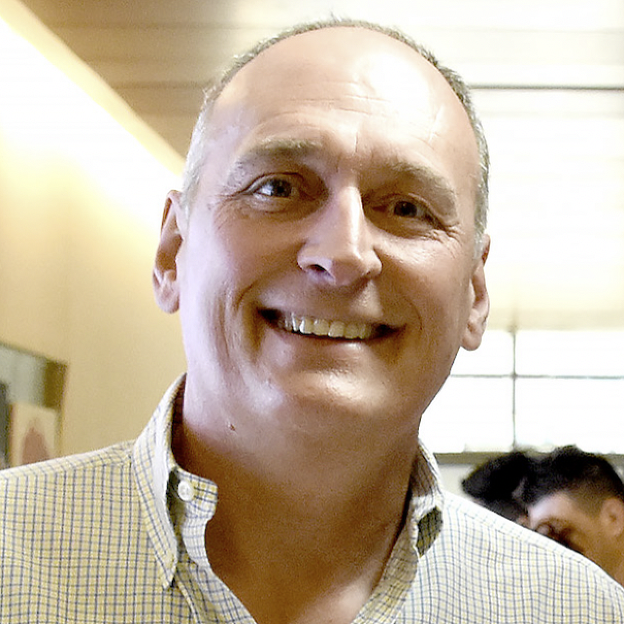

“It appears that the cells responsible for producing certain proteins called cytokines are not being stimulated to produce them where they are needed,” said Vicente Planelles, Ph.D., the study’s senior author and a professor of pathology at U of U Health.

“We propose that cells producing these cytokines are either immunologically exhausted or are possibly dying and are not there to be stimulated in the first place.”

The study, which was conceived and led by Elizabeth S.C.P. Williams, Ph.D., a former graduate student in Planelles’ lab, appears in the Journal of Clinical and Cellular Immunology. The finding could eventually lead to new treatments for long COVID, Planelles said.

Research leads to unexpected finding

Vicente Planelles, Ph.D., the study’s senior author and a professor of pathology at U of U Health.

Previous research by other scientists detected cytokines that are overactive in long COVID patients, which they suggest lead to prolonged inflammation and the onset of long COVID. Elevated cytokine levels and lingering inflammation are also associated other possible post-viral infections such as chronic fatigue syndrome.

Like the earlier researchers, the U of U Health scientists suspected that abnormal and elevated levels of cytokines were a driving force behind long COVID. This was the main theory prompting their study.

To test this theory, Williams, Planelles, and colleagues analyzed blood samples from 12 women who had confirmed cases of long COVID and from 15 men and women who had either never had COVID-19 or had recovered from the infection without lingering symptoms.

To their surprise, they found that, compared with the healthy volunteers, individuals with long COVID had undetectable levels of two cytokines involved in repair of damaged tissue and a 70% decrease in another cytokine that promotes inflammation in body tissue.

“These results were surprising because better known post-viral syndromes caused by other viruses are thought to be triggered by an increase in cytokines that increase and prolong inflammation in the body,” Williams said.

Elizabeth S.C.P. Williams, Ph.D., a former graduate student in Planelles’ lab, conceived and led the study.

“The same sort of pro-inflammatory cytokine process was detected in early studies of long COVID as well,” Williams adds. “But in our study, we detect an opposite result––that the activity of at least four pro-inflammatory cytokines is diminished or nonexistent.”

Planelles, Williams, and colleagues theorize that the drop occurs because the immune cells responsible for producing these cytokines are exhausted during COVID-19 infection and no longer capable of secreting them.

As a result, damaged cells in the lungs and other organs can’t be properly repaired, even after the infection subsides. In turn, long COVID symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, coughing, and fatigue solidify their grip.

“The damage done by the initial viral infection isn’t being healed properly,” postulates Williams, who is receiving post-doctoral training in hematology in another U of U Health lab. “Damaged tissue is a source of inflammation. If the damage persists, so will the inflammation, and you’ll continue to have symptoms.

Further studies needed

The researchers found no significant differences between healthy men and women in 12 of the 13 cytokines measured. Compared to healthy women in the study, females with long COVID had similar reductions in cytokine activity as in the original analysis, which included both men and women.

The findings are based on a small sample size and should be replicated in a larger study, Planelles said. The study also did not determine if different strains of SARS-CoV2 had any influence on cytokines, nor did it account for possible regional differences in causes of long COVID.

“This study was conducted in Utah, a very specific area of the country,” Planelles said. “Perhaps in other geographical areas there may be other mechanisms leading to onset of long COVID. So, this could be one of the ways, but perhaps not the only way, that could lead to this persistent problem.”

In fact, Planelles notes that other scientists are looking at many different ways that autoimmunity, damaged tissue, or tiny blood clots can contribute to the onset of long COVID. In theory, these problems can arise independently or interact with each other to provoke lingering symptoms.

###

This work was supported by the University of Utah Inflammation, Immunology, and Infectious Diseases (3i) Initiative’s Emerging Infectious Diseases Fellowship (recipient, ESCPW) and by a seed grant from the University of Utah Vice President for Research and the Immunology, Inflammation, and Infectious Disease Initiative (recipient, VP). VP and MC were supported by NIH GRANT 5R01-AI143567.